Two years on, Ayushman Bharat has ground to cover on universal health care

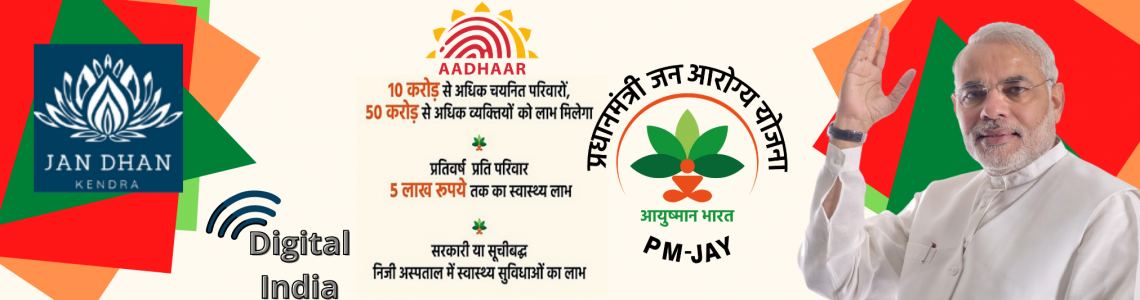

The Centre’s flagship Ayushman Bharat health insurance programme has completed two years. But this time, the buzz around the milestone has been low-key, coming at a time when hospitals are coping with the surge in Covid-19 numbers.

Launched on September 23, 2018, in Ranchi, the Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana has seen over 1.26 crore hospitalisations, involving a spend of over ₹15,772 crore to cover these healthcare bills. In fact, Health Minister Dr Harsh Vardhan said the two-year milestone is as significant as his involvement with polio eradication efforts in the country.

The National Health Authority’s Chief Executive Dr Indu Bhushan said, at an event to herald the two-year milestone, over 23,311 hospitals were on board the scheme covering over 1,500 procedures. The scheme has generated savings to the tune of ₹30,000 crore, he said.

But the scheme still has ground to cover in terms of being more universal in its coverage, say public health voices, even as private healthcare representatives seek greater dialogue to “iron out the wrinkles”.

Exclusion

Making a case for universal healthcare, KM Gopakumar with the Third World Network, points out that a bulk of the middle class remains outside the scheme. And the “package system”, where a set number of procedures are covered for reimbursement by the government, leads to further exclusion of ailments and people, he said.

The scheme is the first step towards providing universal healthcare, said Dr Sudarshan Ballal, Chairman, Manipal Health Enterprises. “Not just the Western nations, but even countries such as Thailand have a well-developed healthcare system,” said Dr Ballal, who is also a former president of NATHEALTH, a platform for hospitals, diagnostics, insurance providers etc.

The last six-odd months have been low-key, he admits, as all efforts have been redirected to tackling Covid. But the effort now should be to dialogue with private providers, address their viability problems and encourage more low-cost or no-frills hospitals, upscaling of teaching hospitals, and even private-private partnerships like the one Manipal Health has with the Tata’s hospital in Jamshedpur for clinical training, he said.

Private players ask for more support

In the early days of the scheme, the pricing of procedures had been a major bone of contention for private healthcare providers, including smaller nursing homes run by medical professionals. In fact, Ballal says, large corporate hospitals are still not entirely participating in the scheme for these reasons.

Lauding the concept of wellness centres, he said there should be attention on prevention and greater screening at the primary centres before a patient lands up at a tertiary care hospital. Hospitals will be willing to get more involved if there was a viability-gap funding mechanism to help hospitals support low-cost procedures. Other alternatives that private healthcare providers have been suggesting to the government include a differential pricing of sorts to support cross-subsidisation of those who cannot pay, by those who can.

Patient woes

Patient experiences, though, include difficulties in getting covered when there are repeated procedures, for instance, as in a chemotherapy that has multiple cycles; or when they travel to a different State for treatment. Presently, Odisha, West Bengal and Telangana are not part of the scheme. These are some of the ground realities the scheme will have to fix, so it can deliver the benefit it sets out to provide.

2089 Comment(s)

sasa

Thanks for every other informative site. The place else may just I get that kind of information written in such an ideal means? I have a venture that I’m just now operating on, and I have been on the look out for such information.

Hello There. I found your blog using msn. This is an extremely well written article. I will be sure to bookmark it and return to read more of your useful information. Thanks for the post. I’ll certainly comeback.

This is very interesting content! I have thoroughly enjoyed reading your points and have come to the conclusion that you are right about many of them. You are great.

Is it okay to post part of this on my website basically post a hyperlink to this webpage?

Your music is amazing. You have some very talented artists. I wish you the best of success.

It is imperative that we read blog post very carefully. I am already done it and find that this post is really amazing.

Wow i can say that this is another great article as expected of this blog.Bookmarked this site..

Document thrilled along with the researching you will designed to makes precise put up impressive. Delightful adventure!

I simply reckoned it is an outline to share in case other companies was first experiencing difficulty looking for still Now i'm a small amount of doubting generally if i here's permitted to use artists and additionally explains relating to right.

With thanks to get furnishing recently available posts in connection with the dilemma, I actually look ahead to learn extra.

Absolutely fantastic posting! Lots of useful information and inspiration, both of which we all need!Relay appreciate your work.

This is really a nice and informative, containing all information and also has a great impact on the new technology. Thanks for sharing it

i read a lot of stuff and i found that the way of writing to clearifing that exactly want to say was very good so i am impressed and ilike to come again in future..

Wonderful article, thanks for putting this together! This is obviously one great post. Thanks for the valuable information and insights you have so provided here.

Really special blog post, Thanks for your time designed for writing It education. Outstandingly drafted guide, if only every webmasters marketed the exact same a better standard of subject matter whilst you, cyberspace was obviously a better set. Satisfy continue the good work!

I think this is an informative post and it is very useful and knowledgeable. therefore, I would like to thank you for the efforts you have made in writing this article.

Decent Blog post, My group is a good believer on advertisment observations at online sites to help you allow web log people know they’ve applied a product favorable to help you the online world!

I've lately began the weblog, the data a person supply on this website offers assisted me personally significantly. Many thanks with regard to all your period & function.

thank you for your interesting infomation.

Thank you regarding offering latest revisions about the problem, My partner and i enjoy examine a lot more.

This was really an interesting topic and I kinda agree with what you have mentioned here!

Please continue this great work and I look forward to more of your awesome blog posts.

Thank you for taking the time to publish this information very useful!

This is a great inspiring article.I am pretty much pleased with your good work.You put really very helpful information...

This is a great inspiring article.I am pretty much pleased with your good work.You put really very helpful information...

This type of message always inspiring and I prefer to read quality content, so happy to find good place to many here in the post, the writing is just great, thanks for the post.

Thank you very much for this useful article. I like it.

Interesting post. I Have Been wondering about this issue, so thanks for posting. Pretty cool post.It 's really very nice and Useful post.Thanks

I like this post,And I guess that they having fun to read this post,they shall take a good site to make a information,thanks for sharing it to me.

It proved to be Very helpful to me and I am sure to all the commentators here!

Thank you for the update, very nice site..

This is my first time i visit here. I found so many interesting stuff in your blog especially its discussion. From the tons of comments on your articles, I guess I am not the only one having all the enjoyment here! keep up the good work

Someone Sometimes with visits your blog regularly and recommended it in my experience to read as well. The way of writing is excellent and also the content is top-notch. Thanks for that insight you provide the readers!

I think that thanks for the valuabe information and insights you have so provided here.

Love what you're doing here guys, keep it up!..

May possibly fairly recently up and running an important web log, the data one offer you on this web site contains given a hand to all of us substantially. Bless you designed for your current precious time & get the job done.

This really which means delightful not to mention original. I just absolutely adore typically the styles not to mention anyone who will become it again in your mailing could be cheerful.

Thanks for sharing nice information with us. i like your post and all you share with us is uptodate and quite informative, i would like to bookmark the page so i can come here again to read you, as you have done a wonderful job.

Thanks you very much for sharing these links. Will definitely check this out..

Positive site, where did u come up with the information on this posting? I'm pleased I discovered it though, ill be checking back soon to find out what additional posts you include.

These are some great tools that i definitely use for SEO work. This is a great list to use in the future..

I can see that you are an expert at your field! I am launching a website soon, and your information will be very useful for me.. Thanks for all your help and wishing you all the success in your business.

Really special blog post, Thanks for your time designed for writing It education. Outstandingly drafted guide, if only every webmasters marketed the exact same a better standard of subject matter whilst you, cyberspace was obviously a better set. Satisfy continue the good work!

If you're into sports betting, 토토사이트 is definitely worth checking out.

All the info I need is right there on 오피가이드 이야기

The 오피 booking system is smoother than any app I’ve tried

I found my favorite massage shop thanks to 오피가이드

Thanks, that was a really cool read!

티비위키 has every drama I love

Thanks to 오피가이드, I found a trusted massage site nearby.

Essentially I actually learn them a short while ago nonetheless I had put together quite a few opinions regarding this now Needed to read simple things them just as before for the reason that it is well crafted.

I always check op사이트 순위 before booking any massage service

탑걸주소 connects me with a community passionate about Japanese media.

Reduce financial stress using 카드 현금화.

Wonderful posting, Thanks a ton to get spreading The following awareness. Wonderfully authored posting, doubts all of blog owners available precisely the same a higher standard subject material just like you, online has got to be improved site. I highly recommend you stay the best!

클라우드 기반 링크모음으로 여러 기기에서 동시에 접근하는 게 좋아요.

Them believes magnificent to read simple things these enlightening plus exceptional reports against your web pages.

Regards for the purpose of post this amazing piece of writing! I recently came across yuor web blog perfect for your preferences. It includes marvelous not to mention advantageous items. Cultivate monetary management give good results!

In reality That i look over it all not long ago however , I saw it certain thinkings about that and after this I want to read the paper it all for a second time given that it's well written.

SR Risk Management Private Investigator certified in various types of private investigation in Malaysia like matrimonial, infidelity, matrimony detective.

오피스타 helped my company reduce overhead costs on office supplies.

I love the variety of genres covered on 티비위키; there's something for everyone.

무료실시간스포츠중계 is the ultimate hack for live sports streaming.

EDEBEX propose un service innovant et très réactif de financement à la facture via sa plateforme de cession et revente de factures.

I can't imagine going anywhere else for a massage now that I've found 오피스타.

https://fullservicelavoro.jimdosite.com/

http://treeads.nation2.com/

https://jumperads.yolasite.com/

http://jumperads.nation2.com/

http://transferefurniture.hatenablog.com

https://atar-almadinah.weebly.com/

https://allmoversinriyadh.wordpress.com/

https://allmoversinriyadh.wordpress.com/2022/04/09/%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a9-%d8%aa%d9%86%d8%b8%d9%8a%d9%81-%d8%a8%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b1%d9%8a%d8%a7%d8%b6-%d9%85%d8%ac%d8%b1%d8%a8%d8%a9/

https://allmoversinriyadh.wordpress.com/2022/04/07/%d8%a7%d9%81%d8%b6%d9%84-%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a9-%d8%aa%d9%86%d8%b8%d9%8a%d9%81-%d8%a8%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b1%d9%8a%d8%a7%d8%b6/

https://allmoversinriyadh.wordpress.com/2022/05/13/%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a9-%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d8%b9%d9%81%d8%b4-%d9%88%d8%ba%d8%b1%d9%81-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%86%d9%88%d9%85-%d8%a8%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b1%d9%8a%d8%a7%d8%b6/

https://companymoversinjeddah.wordpress.com/

https://moversfurniture2018.wordpress.com/2018/12/30/%D8%A7%D9%87%D9%85-%D9%85%D9%83%D8%A7%D8%AA%D8%A8-%D9%88%D9%85%D8%A4%D8%B3%D8%B3%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D8%A8%D8%AC%D8%A7%D8%B2%D8%A7%D9%86/

https://moversriyadhcom.wordpress.com/

https://moversmedina.wordpress.com/

https://moversfurniture2018.wordpress.com/

https://moversmecca.wordpress.com/

https://khairyayman74.wordpress.com/

https://companymoversmecca.home.blog/

https://companymoverstaif.home.blog/

https://companymoverskhamismushit.home.blog/

https://whitear.home.blog/

https://companyhouseservice.wordpress.com/

http://bestmoversfurniture.wordpress.com/

https://companymoversjeddah.wordpress.com/

https://companycleaning307819260.wordpress.com/

https://companymoversriydah.wordpress.com/

https://ataralmadinah662300791.wordpress.com/

https://ataralmadinah662300791.wordpress.com/2022/02/05/%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a9-%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d8%b9%d9%81%d8%b4-%d8%a8%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b1%d9%8a%d8%a7%d8%b6/

https://ataralmadinah662300791.wordpress.com/2022/04/12/%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%B6-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%89-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AF%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%85/

https://groups.google.com/g/moversfurniture/c/wwQFSNvgyAI

https://groups.google.com/g/moversfurniture/c/4L1oHETS4mQ

https://nowewyrazy.uw.edu.pl/profil/khairyayman

https://companyhouseservice.wordpress.com/2022/08/06/%d8%a7%d9%81%d8%b6%d9%84-%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a9-%d8%aa%d9%86%d8%b8%d9%8a%d9%81-%d8%a8%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b1%d9%8a%d8%a7%d8%b6/

https://ataralmadinah662300791.wordpress.com/ شركة الصقر الدولي لنقل العفش والاثاث وخدمات التنظيف المنزلية

شركة مكافحة حشرات بينبع وكذلك شركة كشف تسربات المياه بينبع وتنظيف خزانات وتنظيف الموكيت والسجاد والكنب والشقق والمنازل بينبع وتنظيف الخزانات بينبع وتنظيف المساجد بينبع شركة تنظيف بينبع تنظيف المسابح بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/anti-insects-company-yanbu.html شركة مكافحة حشرات بينبع

httsp://jumperads.com/yanbu/water-leaks-detection-company-yanbu.html شركة كشف تسربات بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/yanbu-company-surfaces.html شركة عزل اسطح بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/yanbu-company-sewage.html شركة تسليك مجاري بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/yanbu-cleaning-company-sofa.html شركة تنظيف كنب بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/yanbu-cleaning-company-mosques.html شركة تنظيف مساجد بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/yanbu-cleaning-company-Carpet.html شركة تنظيف سجاد بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/yanbu-cleaning-company-tanks.html شركة تنظيف خزانات بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/yanbu-cleaning-company-swimming-bath.html شركة تنظيف وصيانة مسابح بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/yanbu-cleaning-company-Furniture.html شركة تنظيف الاثاث بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/yanbu-cleaning-company-home.html شركة تنظيف شقق بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/yanbu-cleaning-company-Carpets.html شركة تنظيف موكيت بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/yanbu-cleaning-company.html شركة تنظيف مجالس بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/yanbu-cleaning-company-house.html شركة تنظيف منازل بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/yanbu-cleaning-company-Villas.html شركة تنظيف فلل بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/yanbu-cleaning-company-curtains.html شركة تنظيف ستائر بينبع

https://jumperads.com/yanbu/yanbu-company-tile.html شركة جلي بلاط بينبع

شركة مكافحة حشرات بالجبيل وكذلك شركة كشف تسربات المياه بالجبيل وتنظيف خزانات وتنظيف الموكيت والسجاد والكنب والشقق والمنازل بالجبيل وتنظيف الخزانات بالجبيل وتنظيف المساجد بالجبيل شركة تنظيف بالجبيل تنظيف المسابح بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/anti-insects-company-jubail.html شركة مكافحة حشرات بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/water-leaks-detection-company-jubail.html شركة كشف تسربات بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/jubail-company-surfaces.html شركة عزل اسطح بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/jubail-company-sewage.html شركة تسليك مجاري بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/jubail-cleaning-company-sofa.html شركة تنظيف كنب بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/jubail-cleaning-company-mosques.html شركة تنظيف مساجد بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/jubail-cleaning-company-Carpet.html شركة تنظيف سجاد بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/jubail-cleaning-company-tanks.html شركة تنظيف خزانات بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/jubail-cleaning-company-swimming-bath.html شركة تنظيف وصيانة مسابح بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/jubail-cleaning-company-Furniture.html شركة تنظيف الاثاث بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/jubail-cleaning-company-home.html شركة تنظيف شقق بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/jubail-cleaning-company-Carpets.html شركة تنظيف موكيت بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/jubail-cleaning-company.html شركة تنظيف مجالس بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/jubail-cleaning-company-house.html شركة تنظيف منازل بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/jubail-cleaning-company-curtains.html شركة تنظيف ستائر بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/jubail-cleaning-company-Villas.html شركة تنظيف فلل بالجبيل

https://jumperads.com/jubail/jubail-company-tile.html شركة جلي بلاط بالجبيل

https://emc-mee.com/blog.html شركات نقل العفش

اهم شركات كشف تسربات المياه بالدمام كذلك معرض اهم شركة مكافحة حشرات بالدمام والخبر والجبيل والخبر والاحساء والقطيف كذكل شركة تنظيف خزانات بجدة وتنظيف بجدة ومكافحة الحشرات بالخبر وكشف تسربات المياه بالجبيل والقطيف والخبر والدمام

https://emc-mee.com/cleaning-company-yanbu.html شركة تنظيف بينبع

https://emc-mee.com/blog.html شركة نقل عفش

اهم شركات مكافحة حشرات بالخبر كذلك معرض اهم شركة مكافحة حشرات بالدمام والخبر والجبيل والخبر والاحساء والقطيف كذلك شركة رش حشرات بالدمام ومكافحة الحشرات بالخبر

https://emc-mee.com/anti-insects-company-dammam.html شركة مكافحة حشرات بالدمام

شركة تنظيف خزانات بجدة الجوهرة من افضل شركات تنظيف الخزانات بجدة حيث ان تنظيف خزانات بجدة يحتاج الى مهارة فى كيفية غسيل وتنظيف الخزانات الكبيرة والصغيرة بجدة على ايدى متخصصين فى تنظيف الخزانات بجدة

https://emc-mee.com/tanks-cleaning-company-jeddah.html شركة تنظيف خزانات بجدة

https://emc-mee.com/water-leaks-detection-isolate-company-dammam.html شركة كشف تسربات المياه بالدمام

https://emc-mee.com/ شركة الفا لنقل عفش واثاث

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-jeddah.html شركة نقل عفش بجدة

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-almadina-almonawara.html شركة نقل عفش بالمدينة المنورة

https://emc-mee.com/movers-in-riyadh-company.html شركة نقل اثاث بالرياض

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-dammam.html شركة نقل عفش بالدمام

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-taif.html شركة نقل عفش بالطائف

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-mecca.html شركة نقل عفش بمكة

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-yanbu.html شركة نقل عفش بينبع

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-alkharj.html شركة نقل عفش بالخرج

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-buraydah.html شركة نقل عفش ببريدة

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-khamis-mushait.html شركة نقل عفش بخميس مشيط

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-qassim.html شركة نقل عفش بالقصيم

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-tabuk.html شركة نقل عفش بتبوك

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-abha.html شركة نقل عفش بابها

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-najran.html شركة نقل عفش بنجران

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-hail.html شركة نقل عفش بحائل

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-dhahran.html شركة نقل عفش بالظهران

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-kuwait.html شركة نقل عفش بالكويت

https://emc-mee.com/price-transfer-furniture-in-khamis-mushit.html اسعار شركات نقل عفش بخميس مشيط

https://emc-mee.com/numbers-company-transfer-furniture-in-khamis-mushit.html ارقام شركات نقل عفش بخميس مشيط

https://emc-mee.com/new-company-transfer-furniture-in-khamis-mushit.html شركة نقل عفش بخميس مشيط جديدة

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-from-khamis-to-riyadh.html شركة نقل عفش من خميس مشيط الي الرياض

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-from-khamis-mushait-to-mecca.html شركة نقل عفش من خميس مشيط الي مكة

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-from-khamis-mushait-to-jeddah.html شركة نقل عفش من خميس مشيط الي جدة

https://emc-mee.com/transfer-furniture-from-khamis-mushait-to-medina.html شركة نقل عفش من خميس مشيط الي المدينة المنورة

https://emc-mee.com/best-10-company-transfer-furniture-khamis-mushait.html افضل 10 شركات نقل عفش بخميس مشيط

https://emc-mee.com/%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D9%87-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D8%A8%D8%AC%D8%AF%D9%87.html

https://emc-mee.com/%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%A7%D8%AB%D8%A7%D8%AB-%D8%A8%D8%AC%D8%AF%D9%87.html

https://saudi-germany.com/ شركة السعودي الالماني للخدمات المنزلية

https://saudi-germany.com/%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d8%aa%d9%86%d8%b8%d9%8a%d9%81-%d8%ae%d8%b2%d8%a7%d9%86%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d8%a8%d8%ac%d8%af%d8%a9/ شركات تنظيف خزانات بجدة

https://saudi-germany.com/%d8%aa%d9%86%d8%b8%d9%8a%d9%81-%d8%ae%d8%b2%d8%a7%d9%86%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d8%a8%d8%ac%d8%af%d8%a9/ تنظيف خزانات بجدة

https://saudi-germany.com/%d8%a7%d9%81%d8%b6%d9%84-%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a9-%d8%aa%d9%86%d8%b8%d9%8a%d9%81-%d8%ae%d8%b2%d8%a7%d9%86%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d8%a8%d8%ac%d8%af%d8%a9/ افضل شركة تنظيف خزانات بجدة

https://saudi-germany.com/%d8%a7%d8%b1%d8%ae%d8%b5-%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a9-%d8%aa%d9%86%d8%b8%d9%8a%d9%81-%d8%ae%d8%b2%d8%a7%d9%86%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d8%a8%d8%ac%d8%af%d8%a9/ ارخص شركة تنظيف خزانات بجدة

https://saudi-germany.com/%d8%ba%d8%b3%d9%8a%d9%84-%d8%ae%d8%b2%d8%a7%d9%86%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d8%a8%d8%ac%d8%af%d8%a9/ غسيل خزانات بجدة

https://saudi-germany.com/%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a9-%d8%aa%d9%86%d8%b8%d9%8a%d9%81-%d8%ae%d8%b2%d8%a7%d9%86%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d8%a8%d8%ac%d8%af%d8%a9/ شركة تنظيف خزانات بجدة

https://saudi-germany.com/cleaning-tanks-company-taif/

https://saudi-germany.com/cleaning-tanks-company-mecca/

https://saudi-germany.com/jumperads-transfer-furniture/

https://saudi-germany.com/%d8%a7%d9%81%d8%b6%d9%84-20-%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a9-%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d8%b9%d9%81%d8%b4-%d8%a8%d9%8a%d9%86%d8%a8%d8%b9-%d8%ae%d8%b5%d9%85-50-%d9%85%d8%b9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%81%d9%83-%d9%88%d8%a7/

https://saudi-germany.com/%d8%a7%d8%b1%d8%ae%d8%b5-%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a9-%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d8%b9%d9%81%d8%b4-%d8%ac%d8%af%d8%a9-%d8%ad%d9%8a-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b5%d9%81%d8%a7/

https://saudi-germany.com/%d8%a7%d8%b1%d8%ae%d8%b5-%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a9-%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d8%b9%d9%81%d8%b4-%d8%ac%d8%af%d8%a9-%d8%a7%d8%a8%d8%ad%d8%b1-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b4%d9%85%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%8a%d8%a9/

https://saudi-germany.com/%d8%a7%d8%b1%d9%82%d8%a7%d9%85-%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d8%b9%d9%81%d8%b4-%d8%a8%d8%ac%d8%af%d8%a9-%d9%85%d8%b9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%aa%d8%ba%d9%84%d9%8a%d9%81/

https://saudi-germany.com/%d8%a7%d8%b1%d8%ae%d8%b5-%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a9-%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d8%b9%d9%81%d8%b4-%d8%a8%d8%ac%d8%af%d8%a9/

https://www.crtmovers.com/

https://www.crtmovers.com/2020/10/transfer-furniture-taif.html شركة نقل اثاث بالطائف

https://www.crtmovers.com/2020/10/transfer-furniture-madina.html

https://www.crtmovers.com/2020/10/movers-madina.html

https://www.crtmovers.com/2020/10/transfer-furniture-riyadh.html

https://www.crtmovers.com/2020/07/transfer-furniture-riyadh.html

https://www.crtmovers.com/2020/05/mecca-transfer-furniture-company-2020.html

https://www.crtmovers.com/2020/05/riyadh-transfer-furniture-company.html

https://www.crtmovers.com/2019/12/jeddah-transfer-furniture.html

https://www.crtmovers.com/2019/12/transfer-furniture-company-jeddah.html

https://www.crtmovers.com/2019/12/transfer-furniture-jeddah-1.html

https://www.crtmovers.com/2019/12/transfer-furniture-taif-1.html

https://www.crtmovers.com/2019/12/transfer-furniture-taif.html

https://www.crtmovers.com/2019/12/price-company-cleaning-tanks-jeddah.html

https://www.crtmovers.com/2019/12/blog-post.html

https://www.crtmovers.com/2019/12/cleaning-tanks-jeddah.html

https://www.crtmovers.com/2023/01/%d8%a7%d9%81%d8%b6%d9%84-%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a9-%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d8%b9%d9%81%d8%b4-%d8%a8%d8%ac%d8%af%d8%a9.html

شركة سكاي لخدمات نقل العفش والاثاث بالمنطقة العربية السعودية نحن نوفر خدمات نقل اثاث بالرياض ونقل عفش بالمدينة المنورة ونقل عفش بمكة ونقل عفش بالطائف نحن نقدم افضل نقل اثاث بخميس مشيط ونقل عفش بجدة

https://treeads.net/ شركة سكاي نقل العفش

https://treeads.net/blog.html مدونة لنقل العفش

https://treeads.net/movers-mecca.html شركة نقل عفش بمكة

https://treeads.net/movers-riyadh-company.html شركة نقل عفش بالرياض

https://treeads.net/all-movers-madina.html شركة نقل عفش بالمدينة المنورة

https://treeads.net/movers-jeddah-company.html شركة نقل عفش بجدة

https://treeads.net/movers-taif.html شركة نقل عفش بالطائف

https://treeads.net/movers-dammam-company.html شركة نقل عفش بالدمام

https://treeads.net/movers-qatif.html شركة نقل عفش بالقطيف

https://treeads.net/movers-jubail.html شركة نقل عفش بالجبيل

https://treeads.net/movers-khobar.html شركة نقل عفش بالخبر

https://treeads.net/movers-ahsa.html شركة نقل عفش بالاحساء

https://treeads.net/movers-kharj.html شركة نقل عفش بالخرج

https://treeads.net/movers-khamis-mushait.html شركة نقل عفش بخميس مشيط

https://treeads.net/movers-abha.html شركة نقل عفش بابها

https://treeads.net/movers-qassim.html شركة نقل عفش بالقصيم

https://treeads.net/movers-yanbu.html شركة نقل عفش بينبع

https://treeads.net/movers-najran.html شركة نقل عفش بنجران

https://treeads.net/movers-hail.html شركة نقل عفش بحائل

https://treeads.net/movers-buraydah.html شركة نقل عفش ببريدة

https://treeads.net/movers-tabuk.html شركة نقل عفش بتبوك

https://treeads.net/movers-dhahran.html شركة نقل عفش بالظهران

https://treeads.net/movers-rabigh.html شركة نقل عفش برابغ

https://treeads.net/movers-baaha.html شركة نقل عفش بالباحه

https://treeads.net/movers-asseer.html شركة نقل عفش بعسير

https://treeads.net/movers-mgmaa.html شركة نقل عفش بالمجمعة

https://treeads.net/movers-sharora.html شركة نقل عفش بشرورة

https://treeads.net/how-movers-furniture-yanbu.html كيفية نقل العفش بينبع

https://treeads.net/price-movers-furniture-yanbu.html اسعار نقل عفش بينبع

https://treeads.net/find-company-transfer-furniture-yanbu.html البحث عن شركات نقل العفش بينبع

https://treeads.net/transfer-furniture-khamis-mushit.html شركات نقل العفش بخميس مشيط

https://treeads.net/how-transfer-furniture-khamis-mushit.html كيفية نقل العفش بخميس مشيط

https://treeads.net/price-transfer-furniture-khamis-mushit.html اسعار نقل عفش بخميس مشيط

https://treeads.net/%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D8%AC%D9%84%D9%8A-%D8%A8%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%B7-%D8%A8%D8%AC%D8%AF%D8%A9.html شركة جلي بلاط بجدة

https://treeads.net/%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D8%AA%D9%86%D8%B8%D9%8A%D9%81-%D9%81%D9%84%D9%84-%D8%A8%D8%AC%D8%AF%D8%A9.html تنظيف فلل بجدة

https://treeads.net/company-transfer-furniture-jazan.html شركة نقل عفش بجازان

https://treeads.net/best-company-cleaning-jeddah-2020.html افضل شركة تنظيف بجدة

https://myspace.com/atarcompany

https://disqus.com/by/atarcompany/about/

https://www.instructables.com/member/dammamcompany64/?publicPreview=true

https://talk.plesk.com/members/atarcompany.414668/#about

https://www.indiegogo.com/individuals/38554392

https://pastebin.com/u/atarcompany

https://giphy.com/channel/atarcompany

https://www.longisland.com/profile/atarcompany

https://lichess.org/@/atarcompany

https://www.gta5-mods.com/users/atarcompany

https://www.divephotoguide.com/user/atarcompany

https://hub.docker.com/u/atarcompany

https://www.custommagnums.com/members/atarcompany.172020/

https://myanimelist.net/profile/atarcompany

https://www.viki.com/users/dammamcompany64_998/overview

https://www.intensedebate.com/people/atarcompany

https://www.designspiration.com/dammamcompany64/

https://www.ted.com/profiles/49307930

https://pbase.com/atarcompany/profile

https://www.producthunt.com/@atar_company

https://audiomack.com/dammamcompany64

https://sketchfab.com/atarcompany

https://www.magcloud.com/user/atarcompany

https://letterboxd.com/atarcompany/

https://speakerdeck.com/atarcompany

https://www.creativelive.com/student/atar-company?via=accounts-freeform_2

https://mastodon.social/@atarcompany

https://talkmarkets.com/member/atarcompany/

https://scioly.org/forums/memberlist.php?mode=viewprofile&u=157215

https://triberr.com/atarcompany

https://www.hackerearth.com/@dammamcompany64/

https://www.thelaw.com/members/atarcompany.140292/#about

https://www.affilorama.com/member/atarcompany

https://hashnode.com/@atarcompany

https://spinninrecords.com/profile/atarcompany

https://www.noteflight.com/profile/6f02598b164b4ae857e4a88552486a9678528bd6

https://www.diggerslist.com/atarcompany/about

https://developers.oxwall.com/user/atarcompany

https://www.metal-archives.com/users/atarcompany

https://www.ezistreet.com/profile/atarcompany/about

https://app.giveffect.com/users/1598877-atarcompany

https://www.mapleprimes.com/users/atarcompany

https://youmagine.com/atarcompany

https://app.zintro.com/profile/atarcompany

https://qiita.com/atarcompany

https://www.codechef.com/users/atarcompany

https://forums.giantitp.com/member.php?346420-atarcompany

https://www.f6s.com/company-dammam

https://www.mobafire.com/profile/atarcompany-1193728?profilepage

https://creator.wonderhowto.com/atarcompany/

https://www.openstreetmap.org/user/atarcompany

https://www.mightycause.com/profile/gs8xbg

https://www.warriorforum.com/members/company%20dammam.html?utm_source=internal&utm_medium=user-menu&utm_campaign=user-profile

https://www.behance.net/companydammam

https://trello.com/u/companydammam/

https://www.scca.com/atarcompany

http://www.domyate.com/2019/08/27/transfer-furniture-north-riyadh/ نقل عفش شمال الرياض

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/05/movers-company-khamis-mushait/ شركات نقل عفش بخميس مشيط

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/05/10-company-transfer-furniture-khamis-mushait/ شركة نقل العفش بخميس مشيط

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/05/all-transfer-furniture-khamis-mushait/ شركات نقل اثاث بخميس مشيط

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/05/best-company-transfer-furniture-khamis-mushit/ افضل شركات نقل اثاث بخميس مشيط

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/05/company-transfer-furniture-khamis-mushit/ شركات نقل اثاث بخميس مشيط

http://www.domyate.com/category/%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D8%AC%D8%AF%D8%A9/ نقل عفش جدة

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/25/movers-furniture-from-jeddah-to-jordan/ نقل عفش من جدة الي الاردن

http://www.domyate.com/2019/10/03/price-cleaning-tanks-in-jeddah/ اسعار شركات تنظيف خزانات بجدة

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/25/movers-furniture-from-jeddah-to-egypt/ نقل عفش من جدة الي مصر

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/24/movers-furniture-from-jeddah-to-lebanon/ نقل عفش من جدة الي لبنان

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/22/%d8%a3%d9%86%d8%ac%d8%ad-%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d8%a7%d8%ab%d8%a7%d8%ab-%d8%a8%d8%ac%d8%af%d8%a9/ شركات نقل اثاث بجدة

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/22/best-company-movers-jeddah/ افضل شركات نقل اثاث جدة

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/22/company-transfer-furniture-yanbu/ شركات نقل العفش بينبع

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/21/taif-transfer-furniture-company/ شركة نقل عفش في الطائف

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/21/%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b9%d9%81%d8%b4/ شركات نقل العفش

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/21/%d8%b7%d8%b1%d9%82-%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b9%d9%81%d8%b4/ طرق نقل العفش

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/20/%d8%ae%d8%b7%d9%88%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b9%d9%81%d8%b4-%d9%88%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%a7%d8%ab%d8%a7%d8%ab/ خطوات نقل العفش والاثاث

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/20/best-10-company-transfer-furniture/ افضل 10 شركات نقل عفش

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/20/%d9%83%d9%8a%d9%81-%d9%8a%d8%aa%d9%85-%d8%a7%d8%ae%d8%aa%d9%8a%d8%a7%d8%b1-%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b9%d9%81%d8%b4-%d9%88%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%a7%d8%ab%d8%a7%d8%ab/ اختيار شركات نقل العفش والاثاث

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/20/cleaning-company-house-taif/ شركة تنظيف منازل بالطائف

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/20/company-cleaning-home-in-taif/ شركة تنظيف شقق بالطائف

http://www.domyate.com/2019/09/20/taif-cleaning-company-villas/ شركة تنظيف فلل بالطائف

http://www.domyate.com/ شركة نقل عفش

http://www.domyate.com/2017/09/21/%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%AE%D8%B2%D9%8A%D9%86/ نقل العفش والتخزين

http://www.domyate.com/2016/07/02/transfer-furniture-dammam شركة نقل عفش بالدمام

http://www.domyate.com/2015/11/12/%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%AF%D9%8A%D9%86%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D9%86%D9%88%D8%B1%D8%A9/ شركة نقل عفش بالمدينة المنورة

http://www.domyate.com/2016/06/05/transfer-furniture-jeddah/ شركة نقل عفش بجدة

http://www.domyate.com/2017/08/10/movers-company-mecca-naql/ شركات نقل العفش بمكة

http://www.domyate.com/2016/06/05/transfer-furniture-mecca/ شركة نقل عفش بمكة

http://www.domyate.com/2016/06/05/transfer-furniture-taif/ شركة نقل عفش بالطائف

http://www.domyate.com/2016/06/05/transfer-furniture-riyadh/ شركة نقل عفش بالرياض

http://www.domyate.com/2016/06/05/transfer-furniture-yanbu/ شركة نقل عفش بينبع

http://www.domyate.com/category/%D8%AE%D8%AF%D9%85%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%AE%D8%B2%D9%8A%D9%86/ نقل العفش والتخزين

http://www.domyate.com/2015/08/30/furniture-transport-company-in-almadinah/ شركة نقل عفش بالمدينة المنورة

http://www.domyate.com/2016/06/05/transfer-furniture-medina-almonawara/ شركة نقل عفش بالمدينة المنورة

http://www.domyate.com/2018/10/13/%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D8%AC%D8%AF%D8%A9-%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D9%85%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%B2%D8%A9/ نقل عفش بجدة

http://www.domyate.com/2016/07/22/%d8%a7%d8%b1%d8%ae%d8%b5-%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a9-%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d8%b9%d9%81%d8%b4-%d8%a8%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%85%d8%af%d9%8a%d9%86%d8%a9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%85%d9%86%d9%88%d8%b1%d8%a9/ ارخص شركة نقل عفش بالمدينة المنورة

http://www.domyate.com/2016/07/25/%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%82%D8%B5%D9%8A%D9%85/ شركة نقل عفش بالقصيم

http://www.domyate.com/2016/07/25/%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D8%A8%D8%AE%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%B3-%D9%85%D8%B4%D9%8A%D8%B7/ شركة نقل عفش بخميس مشيط

http://www.domyate.com/2016/07/25/%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%A8%D9%87%D8%A7/ شركة نقل عفش بابها

http://www.domyate.com/2016/07/23/%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D8%A8%D8%AA%D8%A8%D9%88%D9%83/ شركة نقل عفش بتبوك

شركة كيان لنقل العفش بالرياض والمدينة المنورة وجدة ومكة والطائف والدمام تقديم لكم دليل كامل لشركات نقل العفش بالمملكة العربية السعودية

https://mycanadafitness.com/ شركة كيان لنقل العفش

https://mycanadafitness.com/forum.html منتدي نقل العفش

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnitureriyadh.html شركة نقل اثاث بالرياض

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurniturejaddah.html شركة نقل اثاث بجدة

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnituremecca.html شركة نقل اثاث بمكة

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnituretaif.html شركة نقل اثاث بالطائف

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnituremadina.html شركة نقل اثاث بالمدينة المنورة

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnituredammam.html شركة نقل اثاث بالدمام

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurniturekhobar.html شركة نقل اثاث بالخبر

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnituredhahran.html شركة نقل اثاث بالظهران

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurniturejubail.html شركة نقل اثاث بالجبيل

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnitureqatif.html شركة نقل اثاث بالقطيف

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnitureahsa.html شركة نقل اثاث بالاحساء

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurniturekharj.html شركة نقل اثاث بالخرج

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurniturekhamismushit.html شركة نقل اثاث بخميس مشيط

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnitureabha.html شركة نقل اثاث بابها

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurniturenajran.html شركة نقل اثاث بنجران

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurniturejazan.html شركة نقل اثاث بجازان

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnitureasir.html شركة نقل اثاث بعسير

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurniturehail.html شركة نقل اثاث بحائل

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnitureqassim.html شركة نقل عفش بالقصيم

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnitureyanbu.html شركة نقل اثاث بينبع

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnitureburaidah.html شركة نقل عفش ببريدة

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurniturehafralbatin.html شركة نقل عفش بحفر الباطن

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurniturerabigh.html شركة نقل عفش برابغ

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnituretabuk.html شركة نقل عفش بتبوك

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnitureasfan.html شركة نقل عفش بعسفان

https://mycanadafitness.com/movingfurnituresharora.html شركة نقل عفش بشرورة

https://mycanadafitness.com/companis-moving-riyadh.html شركات نقل العفش بالرياض

https://mycanadafitness.com/cars-moving-riyadh.html سيارات نقل العفش بالرياض

https://mycanadafitness.com/company-number-moving-riyadh.html ارقام شركات نقل العفش بالرياض

https://mycanadafitness.com/company-moving-jeddah.html شركات نقل العفش بجدة

https://mycanadafitness.com/price-moving-jeddah.html اسعار نقل العفش بجدة

https://mycanadafitness.com/company-moving-mecca.html شركات نقل العفش بمكة

http://fullservicelavoro.com/ شركة ريلاكس لنقل العفش والاثاث

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/07/transfer-movers-taif-furniture/ شركة نقل عفش بالطائف

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/08/transfer-movers-riyadh-furniture/ شركة نقل عفش بالرياض

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/08/transfer-movers-jeddah-furniture/ شركة نقل عفش بجدة

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/01/transfer-and-movers-furniture-mecca/ شركة نقل عفش بمكة

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/07/transfer-movers-madina-furniture/ شركة نقل عفش بالمدينة المنورة

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/07/transfer-movers-khamis-mushait-furniture/ شركة نقل عفش بخميس مشيط

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/09/transfer-movers-abha-furniture/ شركة نقل اثاث بابها

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/07/transfer-movers-najran-furniture/ شركة نقل عفش بنجران

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/16/transfer-movers-hail-furniture/ ِشركة نقل عفش بحائل

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/16/transfer-movers-qassim-furniture/ شركة نقل عفش بالقصيم

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/02/02/transfer-movers-furniture-in-bahaa/ شركة نقل عفش بالباحة

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/13/transfer-movers-yanbu-furniture/ شركة نقل عفش بينبع

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/18/%d8%af%d9%8a%d9%86%d8%a7-%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d8%b9%d9%81%d8%b4-%d8%a8%d8%a7%d8%a8%d9%87%d8%a7/ دينا نقل عفش بابها

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/13/%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AB%D8%A7%D8%AB-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%AF%D9%8A%D9%86%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D9%86%D9%88%D8%B1%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%87%D9%85-%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A7%D8%AA/ نقل الاثاث بالمدينة المنورة

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/12/%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%AE%D8%B5-%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D8%A8%D9%85%D9%83%D8%A9/ ارخص شركة نقل عفش بمكة

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/07/transfer-movers-elkharj-furniture/ شركة نقل عفش بالخرج

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/01/07/transfer-movers-baqaa-furniture/ شركة نقل عفش بالبقعاء

http://fullservicelavoro.com/2019/02/05/transfer-furniture-in-jazan/ شركة نقل عفش بجازان

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-mecca

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/home

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-jedaah-elhamdniah

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-yanbu

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-najran

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-Jizan

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/jazan

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/taif

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/moversjeddah

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-abha

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-elahsa

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-elkhobar

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-elkharj

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-elmadina-elmnowara

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-eljubail

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-elqassim

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-hafrelbatin

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-elbaha

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-jeddah

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-dammam

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-taif

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-burydah

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-tabuk

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-hail

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-khamis-mushait

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/movers-rabigh

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/madina

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/mecca

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/dammam

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/jeddah

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/ahsa

https://sites.google.com/view/movers-riyadh/cleaning-mecca

https://movingsaudia.over-blog.com/

https://sakr-eg.jimdosite.com/blog/shrk-nql-aafsh-bmk/

https://emc-mee.jimdosite.com/blog/moving-furniture-abha/

https://emc-mee.jimdosite.com/

https://emc-mee.jimdosite.com/blog/cleaning-jeddah/

https://emc-mee.jimdosite.com/my-services/

https://www.sbnation.com/users/mycanadafitness

https://sakr-eg.jimdosite.com/moving-furniture-jeddah/

https://seg7544.wixsite.com/my-site-1/post/%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D9%88%D8%AA%D8%BA%D9%84%D9%8A%D9%81-%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%A8%D9%87%D8%A7

https://seg7544.wixsite.com/my-site-1

https://companyservice33.weebly.com/blog1/8069015

https://companyservice33.weebly.com/blog1/1275122

https://companyservice33.weebly.com/blog1

https://www.skreebee.com/read-blog/110085

https://telegra.ph/%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%AC%D8%AF%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%89-%D8%AC%D8%A7%D8%B2%D8%A7%D9%86-07-12

https://webyourself.eu/blogs/25649/%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%AC%D8%AF%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%89-%D8%AC%D8%A7%D8%B2%D8%A7%D9%86

https://webyourself.eu/blogs/26016/%D8%A7%D9%81%D8%B6%D9%84-%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%B4-%D8%AC%D8%AF%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D8%A8%D8%AD%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B4%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%A9

https://www.domyate.com/2022/06/14/why-emc-mee-company-to-transfer-furniture-to-to-jeddah/

https://www.domyate.com/2022/06/12/best-nakl-afsh-jeddah/

https://www.domyate.com/2022/06/12/%d9%83%d9%8a%d9%81%d9%8a%d8%a9-%d9%81%d9%83-%d9%88%d8%aa%d8%b1%d9%83%d9%8a%d8%a8-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b9%d9%81%d8%b4-%d9%88%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%a7%d8%ab%d8%a7%d8%ab-%d8%a8%d8%ac%d8%af%d8%a9/

https://telegra.ph/%D8%A7%D9%81%D8%B6%D9%84-%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D8%AA%D9%86%D8%B8%D9%8A%D9%81-%D9%85%D9%83%D9%8A%D9%81%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A8%D9%85%D9%83%D8%A9-07-17

https://www.carookee.de/forum/Retinoblastom-Forum/32167083?mp=156822404062d6023635638289af31b90d4f5bbea03aea79dc802ca&mps=%26%231588%3B%26%231585%3B%26%231603%3B%26%231577%3B+%26%231578%3B%26%231606%3B%26%231592%3B%26%231610%3B%26%231601%3B+%26%231605%3B%26%231603%3B%26%231610%3B%26%231601%3B%26%231575%3B%26%231578%3B+%26%231576%3B%26%231605%3B%26%231603%3B%26%231577%3B#32167083

https://www.carookee.de/forum/Retinoblastom-Forum/32167082?mp=49083704862d5f02883b054f8275606a980b0ddf6bde4bc1a0c4b5&mps=%26%231588%3B%26%231585%3B%26%231603%3B%26%231577%3B+%26%231606%3B%26%231602%3B%26%231604%3B+%26%231593%3B%26%231601%3B%26%231588%3B+%26%231575%3B%26%231604%3B%26%231589%3B%26%231602%3B%26%231585%3B+%26%231575%3B%26%231604%3B%26%231583%3B%26%231608%3B%26%231604%3B%26%231610%3B#32167082

https://www.carookee.de/forum/Retinoblastom-Forum/32167084?mp=156822404062d604da7583a085d6df59451e00fbf675ffe4d767997&mps=%26%231588%3B%26%231585%3B%26%231603%3B%26%231577%3B+%26%231578%3B%26%231606%3B%26%231592%3B%26%231610%3B%26%231601%3B+%26%231582%3B%26%231586%3B%26%231575%3B%26%231606%3B%26%231575%3B%26%231578%3B+%26%231576%3B%26%231582%3B%26%231605%3B%26%231610%3B%26%231587%3B+%26%231605%3B%26%231588%3B%26%231610%3B%26%231591%3B#32167084

https://www.carookee.de/forum/Retinoblastom-Forum/32167085?mp=156822404062d60ab56d77ab711e09fefce9f81dfa2064fdad6969e&mps=%26%231588%3B%26%231585%3B%26%231603%3B%26%231577%3B+%26%231606%3B%26%231602%3B%26%231604%3B+%26%231593%3B%26%231601%3B%26%231588%3B+%26%231605%3B%26%231606%3B+%26%231580%3B%26%231583%3B%26%231577%3B+%26%231575%3B%26%231604%3B%26%231609%3B+%26%231580%3B%26%231575%3B%26%231586%3B%26%231575%3B%26%231606%3B#32167085

https://elasakr-jeddah.jimdosite.com/

https://business.go.tz/web/rashid.ndimbo/~/86020/home/-/message_boards/message/24415721

https://business.go.tz/web/rashid.ndimbo/~/86020/home/-/message_boards/message/24415731

https://business.go.tz/web/rashid.ndimbo/~/86020/home/-/message_boards/message/24458120

https://business.go.tz/web/rashid.ndimbo/~/86020/home/-/message_boards/message/24456486

https://bestmoversfurniture.wordpress.com/2022/04/05/transfer-furniture-jeddah/

https://www.smore.com/ps2zt

https://www.smore.com/s9rz8q

https://www.smore.com/0kthj

https://companyhouseservice.wordpress.com/2022/08/06/%d8%a7%d9%81%d8%b6%d9%84-%d8%b4%d8%b1%d9%83%d8%a9-%d8%aa%d9%86%d8%b8%d9%8a%d9%81-%d8%a8%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b1%d9%8a%d8%a7%d8%b6/

https://topsitenet.com/startpage/ataralmadinah/859508/

https://topsitenet.com/profile/ataralmadinah/859508/

https://en.gravatar.com/elsakrjeddah

https://610b31f1e425e.site123.me/about

https://www.kickstarter.com/profile/atar-almadinah/about

https://500px.com/p/ataralmadinah?view=photos

https://about.me/atar-almadinah/

https://www.behance.net/ataralmadinah/

https://vimeo.com/user163509125

https://www.myminifactory.com/users/atar

https://speakerdeck.com/almadinah

https://www.instructables.com/member/atar-almadinah/

https://www.recode.net/users/ataralmadinah

http://simp.ly/p/bwJRTQ

https://zenwriting.net/jzlzjv7sf2

https://writer.zohopublic.com/writer/published/rg9748fafd0f2210f4604b33d2cbf28388aea

https://my.desktopnexus.com/ataralmadinah/journal/furniture-moving-company-in-jeddah-38820/

https://app.ex.co/stories/item/c9e4da01-b4c3-492f-84a4-55474a6abf47

https://pastelink.net/a93tslol

https://pastelink.net/6zkez7a2

https://www.kongregate.com/accounts/ataralmadinah

https://bit.ly/3PiheFn

https://bit.ly/3SJJZxX

I appreciate the honest and detailed reviews on 오피가이드.

I trust 오피스타 for honest reviews and recommendations.

I wouldn’t trade my visits to 오피아트 for anything.

밤의민족 offers unparalleled access to a variety of massage services.

부산비비기 provides a truly exceptional massage experience.

The massages at 아이러브밤 are consistently excellent and restorative.

대밤 is a treasure trove of amazing massage options.

I appreciate how 오피뷰 makes it simple to find a massage place that suits my needs.

Nine Things That Your Parent Teach You About Car Key Housing Repair Car Key Housing Repair

송도출장마사지 송도지역 24시 송도출장 전문업체 후불제 마사지로 안전하고 편리하게 이용하세요.

강남출장마사지 24시 연중무휴 이제샵에 직접방문하지 않더라도 집에서 편안하게 마사지 받을수 있습니다. 선입금없는 후불제마사지 안심하고 이용하세요

This is a great post. I like this topic.This site has lots of advantage.I found many interesting things from this site. It helps me in many ways.Thanks for posting this again.

시크릿 토닥이 여성전용마사지 대한민국 주요도시 어디든 30분 이내 방문가능한 여성전용 출장마사지 플랫폼

합리적인 가격과 고품격 마사지 서비스로 최고의 만족도를 자랑합니다.

I am so grateful for your blog.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

러블리 인천출장마사지 출장 중 갑자기 몸이 뻐근할 때, 바로 예약했는데 30분 내 도착!

서비스도 친절하고 손기술도 최고였어요.

후불제라서 믿고 이용할 수 있었습니다. 인천출장안마

The tools and equipments used for construction purposes are known as construction tools. Some of the best equipments are used by the corporate companies for constructing buildings.

Everything has its value. Thanks for sharing this informative information with us. GOOD works!

Wow, cool post. I’d like to write like this too – taking time and real hard work to make a great article… but I put things off too much and never seem to get started. Thanks though.

Very informative post! There is a lot of information here that can help any business get started with a successful social networking campaign.

thanks for the tips and information..i really appreciate it..

I have read your article, it is very informative and helpful for me.I admire the valuable information you offer in your articles. Thanks for posting it..

Someone Sometimes with visits your blog regularly and recommended it in my experience to read as well. The way of writing is excellent and also the content is top-notch. Thanks for that insight you provide the readers!

토닥이 여성전용마사지 강남지역에서 이미 입소문난 강남지역 1등 토닥이 여성전용마사지

I would really love to guest post on your blog..**.`

Very efficiently written story. It will be useful to anybody who employess it, including me. Keep up the good work – can’r wait to read more posts.

I am frequently to blogging i really appreciate your content regularly. This content has really peaks my interest. Let me bookmark your internet site and keep checking choosing information.

The tools and equipments used for construction purposes are known as construction tools. Some of the best equipments are used by the corporate companies for constructing buildings.

You must indulge in a contest for one of the greatest blogs over the internet. Ill suggest this web site!

Check out different facilities for beat making online and find out one that suits you best. Beat-making is a popular hobby today. There are a good number of options to combine so you only have to twist and turn.

This internet site is my breathing in, very great pattern and perfect content .

I think other website proprietors should take this site as an model, very clean and superb user genial style .

“this is very interesting. thanks for that. we need more sites like this. i commend you on your great content and excellent topic choices.”

인천 지역 후불제 마사지 이용하려는 분들 도움 되실까 해서 남겨요. 24시간 운영하는 인천출장마사지 러블리 출장안마 정말 좋았습니다.

مواقع جيست بوست جميع المجالات

تبادل باك لينك

هل تريد تبادل باك لينك مع موقع عالي؟

نحن نمتلك 25 رابط دوفلو ذات جودة عالية

من يرغب تبادل باك لينك

يرجي التواصل معنا عبر

004917637777797 الواتس اب

https://www.eljnoub.com/

https://www.eljnoub.com/

https://www.eljnoub.com/

https://www.rauhane.net

https://www.s3udy.org/

https://sexalarab.eu/

https://hurenberlin.com/

https://buybacklink.de/

https://bestbacklinks.de

https://backlinkservices.de

https://www.q8yat.org/

https://www.elso9.com/

https://jalbalhabeb.org

https://wikimedia.cc

https://hurenberlin.com/

https://www.elso9.com/

https://www.eljnoub.com/

https://www.q8yat.org/

https://www.rauhane.net

https://www.jeouzal.org

https://www.alfalaki.net

https://www.jaouzal.org

https://casinoberlin.eu/

https://www.sheikhrohani.de

https://www.myemairat.de

https://www.saudieonline.de

https://www.nejetaa.de

https://www.iesummit.de

https://www.jalbalhabeb.de

https://www.alukah.de

https://www.mqaall.de

https://www.elbalad.de

https://www.muhtwa.de

https://www.mawdoo3.de

https://www.eljnoub.com/category/%d8%ac%d8%b0%d8%a8-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%ad%d8%a8%d9%8a%d8%a8/

https://www.eljnoub.com/category/%d9%84%d8%ac%d8%b0%d8%a8-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%85%d8%ad%d8%a8%d8%a9/

https://www.eljnoub.com/category/%d8%a7%d8%af%d8%b9%d9%8a%d8%a9-%d8%b1%d9%88%d8%ad%d8%a7%d9%86%d9%8a%d8%a9/

https://www.eljnoub.com/category/%d8%a7%d8%b3%d9%84%d8%a7%d9%85%d9%8a%d8%a7%d8%aa/

https://hurenberlin.com/category/huren-modelle/

https://www.eljnoub.com/wp-admin/admin.php?page=wpseo_dashboard

Yes i am totally agreed with this article and i just want say that this article is very nice and very informative article.I will make sure to be reading your blog more. You made a good point but I can't help but wonder, what about the other side? !!!!!!Thanks

eating disorders are of course sometimes deadly because it can cause the degeneration of one’s health,.

마킹 출장마사지, 출장안마 타이마사지, 아로마마사지, 발마사지 등 다양한 마사지 프로그램을 제공합니다. 24시 연중무휴 빠른방문으로 편리하게 이용하세요

The 9 Things Your Parents Taught You About Robotic Vacuum Cleaner Uk Robotic vacuum cleaner uk

You have a real ability for writing unique content. I like how you think and the way you represent your views in this article. I agree with your way of thinking. Thank you for sharing.

I began relying on 주식디비 for better trading strategies. The platform provides detailed insights, accurate updates, and stable performance that supports smarter decisions. I strongly suggest 주식디비 for consistent performance.

Green construction jobs are becoming the norm in the contracting and construction industries, so to remain competitive construction professionals must expand their skill set in the green and eco-friendly building fields. More companies are opting to construct green buildings, with seventy percent of executives and developers making their firms part of sustainability programs for tax breaks and the benefit of reduced operating costs. Financial benefits like these are among the many reasons why green buildings are being built so frequently and why there is a demand for workers and contractors with sustainable construction skills and a familiarity with eco-friendly construction. But what do contractors, journeymen, and construction specialist need to know about working on green buildings?

What a thrilling post. It is extremely chock-full of useful information. Thanks for such a great info.

Thanks for the information provided! I was researching for this article for a long time, but I was not able to see a dependable source.

cheers for such a brilliant website. Where else could someone get that kind of information written in such a perfect way? I have a presentation that I am presently working on, and I have been on the watch out for such information.

Really interesting and special post. I like things such as making more homework, developing writing skills, and also related things. These kinds of secrets help in being a qualified person on this topic. This page is very helpful to myself because people like you committed time to learning. Regularity is the key. But it is not too easy, as has been designed to be. I am not an expert like you and plenty of times I feel really giving it up.

I chose 대리결제 because I needed reliable assistance for online payments. The transaction was completed smoothly, showing how reliable and well-managed the service is. 대리결제 is a great option for people who want stress-free assistance anytime.

Spot lets start on this write-up, I seriously believe this amazing site requirements much more consideration. I’ll more likely once again to read a great deal more, many thanks that info.

I see your point, and I totally appreciate your article. For what its worth I will tell all my friends about it, quite resourceful. Later.

You will be permitted to posting companies, yet not one-way links, except in cases where they can be permitted plus for issue.

RaptorGamingID adalah platform resmi Indonesia yang menawarkan permainan terbaru dan hadiah harian untuk para pemain.

Really interesting and special post. I like things such as making more homework, developing writing skills, and also related things. These kinds of secrets help in being a qualified person on this topic. This page is very helpful to myself because people like you committed time to learning. Regularity is the key. But it is not too easy, as has been designed to be. I am not an expert like you and plenty of times I feel really giving it up.

Wow Da weiss man, wo es hingehen muss Viele Grüsse Mirta

This seems amazing to see this kind of educational as well as distinctive content articles in your web sites.

The Flower Society: trusted online florist in Lebanon. Shop luxury bouquets, roses & orchids with same-day delivery for every occasion.

I in the past left a comment on the web site and selected alert me about latest responses. Perhaps there is a way to eliminate that system? I am getting numerous mails.

This internet web page is genuinely a walk-through for all of the info you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll surely discover it.

This internet web page is genuinely a walk-through for all of the info you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll surely discover it.

This internet web page is genuinely a walk-through for all of the info you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll surely discover it.

This internet web page is genuinely a walk-through for all of the info you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll surely discover it.

This internet web page is genuinely a walk-through for all of the info you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll surely discover it.

true happiness can be difficult to achieve, you can be rich but still not be truly happy,

해피마사지 권선구,팔달구,영통구 등 수원전지역 출장마사지 서비스를 제공하고 있습니다.

호텔,모텔,집 언제 어디서나 편리하게 수원출장안마 서비스를 즐겨보세요 수원출장전문 업체.

the table beds which we have a year ago had already broken down, it is mostly made up of plastic,.

That is very interesting, You are an excessively professional blogger. I’ve joined your feed and stay up for searching for more of your great post. Also, I’ve shared your website in my social networks!

I am impressed. I don't think Ive met anyone who knows as much about this subject as you do. You are truly well informed and very intelligent. You wrote something that people could understand and made the subject intriguing for everyone. Really, great blog you have got here.

숙련된 테라피스트가 직접 방문하는 영등출장마사지 서비스! 스트레스 해소와 피로 회복에 최적화된 영등포출장안마 코스로 힐링하세요.

Understanding domain authority vs page authority is key in SEO. Domain authority measures the strength of an entire website, while page authority focuses on individual page rankings. Knowing the difference between domain authority vs page authority helps marketers build better strategies, improve search rankings, and optimize content for visibility.

But a smiling visitant here to share the love (:, btw great style and design .

Very efficiently written story. It will be useful to anybody who employess it, including me. Keep up the good work – can’r wait to read more posts.

I just wanted to tell you how much my partner and i appreciate anything you’ve discussed to help improve the lives of men and women in this subject matter. Through your current articles, I have gone through just a newcomer to a professional in the area. It’s truly a gratitude to your good work. Thanks Nobel Calling Cards

I’m not sure exactly why but this site is loading very slow for me. Is anyone else having this issue or is it a issue on my end? I’ll check back later on and see if the problem still exists.

Hang in there for eventually you are going to arrive to realise that lifestyle is much more exciting than you actually thought doable and even feel!

Regards for this post, I am a big big fan of this site would like to go on updated.

I truly appreciated this wonderful blog. Make sure you keep up the good work. All the best !!!!

샵으로 직접 방문하지 않아도 어디서나 편안하게 즐기수 있는 영등포출장마사지. 영등포지역 인기마사지 업체 24시연중무휴 합리적인 가격과 수준높은 마사지서비스 제공.

the air compressors that we use at home are the high powered ones, we also use it for cleaning.

The tools and equipments used for construction purposes are known as construction tools. Some of the best equipments are used by the corporate companies for constructing buildings.

부산호빠와 해운대호빠는 부산 유흥 문화에서 특별하고 이색적인 밤을 보낼 수 있는 공간입니다. 특히 해운대호빠는 부산의 대표적인 관광지이자 밤문화 1번지 해운대에서

I looked into how 개인회생DB is presented within structured data discussions. Information shared often addresses classification methods, update cycles, and record maintenance. In conclusion, reviewing neutral references to 개인회생DB provides useful background information.

수원토닥이 빠른 도착과 세심한 관리가 강점인 여성전용출장마사지 서비스로 만족도 높은 마사지를 제공합니다 나만의 공간에서 즐기는 프라이빗 마사지.

This is great content. You’ve loaded this with useful, informative content that any reader can understand. I enjoy reading articles that are so very well-written.

비아그라는 미국 제약사 화이자가 개발한 남성 발기부전 치료제의 상품명으로, 주성분은 실데나필(Sildenafil)입니다. 실데나필은 PDE5 억제제에 속하는

The next time I read a blog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as much as this one. I mean, I know it was my choice to read, but I actually thought youd have something interesting to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something that you could fix if you werent too busy looking for attention.

I reviewed general commentary to better understand the context surrounding 주식DB. Sources frequently mention how information is stored, reviewed, and referenced systematically. Finally, examining mentions of 주식DB helps clarify its role within data-related discussions.

I explored various sources to see how 주식DB is typically explained and categorized. The middle of these discussions usually focuses on operational handling and system organization. Ultimately, observing how 주식DB is referenced helps maintain an unbiased understanding.

4 Dirty Little Tips On The Window Repair & Burglary Repairs Industry double Glazing window Repair

"The Railroad Settlement Colon Cancer Awards: The Best, Worst, And Strangest Things We've Ever Seen Railroad Settlements

Five Killer Quora Answers On Couch With Pullout Bed Couch With Pullout Bed

The 10 Most Terrifying Things About Restoration For Conservatory restoration for conservatory, support.roombird.ru,

15 Things Your Boss Would Like You To Know You Knew About Cleaning Robot Smart Vacuum Cleaner

See What Lung Cancer Louisiana Asbestos Exposure Tricks The Celebs Are Utilizing Lung Cancer Louisiana

French Door Glass Tools To Improve Your Everyday Lifethe Only French Door Glass Trick Every Individual Should Be Able To french door glass (goodwin-Dillard-2.blogbright.net)

You'll Never Guess This Window Screen Repair's Benefits window screen Repair [Https://earthloveandmagic.com/]

Who Is Louisiana Asbestos Exposure And Why You Should Be Concerned Louisiana Asbestos Exposure Lawsuits

You'll Never Guess This Lever Handle Lock Replacement's Secrets lever handle lock replacement

Buzzwords, De-Buzzed: 10 Other Ways To Say Best Cat Flap Installer electronic cat flap installation (oren-expo.ru)

The 10 Most Terrifying Things About Upvc Door Lock Replacement upvc door lock replacement

Local Glazing Company Tools To Ease Your Everyday Lifethe Only Local Glazing Company Trick Every Individual Should Learn Local Glazing Company

You'll Never Guess This Bunk Beds Children's's Secrets Bunk Beds Children's

Think You're Cut Out For Doing Door Knobs Repair? Take This Quiz door knob Repair

9 Things Your Parents Taught You About Residential Window Repair Window Repair

The 10 Scariest Things About Bulit In Oven Bulit in Oven

What's The Current Job Market For Sliding Door Replacement Professionals? Sliding Door Replacement

The Best Couches UK Tricks To Change Your Life Best Couches Uk

You'll Never Be Able To Figure Out This Buy Designer Handmade Sofa's Tricks Buy Designer Handmade Sofa (www.pottomall.com)

Get Meals Internet – Internet Foods Ordering Strategy for Dining establishments

The 9 Things Your Parents Taught You About Conservatory Improvement conservatory Improvement

The 10 Scariest Things About Railroad Settlement Copd Railroad Settlement Copd (https://www.elimuellerleile.top)

14 Cartoons About Economical Cat Flap Installer That'll Brighten Your Day experienced cat flap installers

The Biggest Problem With Fix My Windows And How You Can Resolve It Repair double glazing windows

What's The Current Job Market For Double Glazing Repair Professionals? double glazing repair

See What High Security Door Locks Tricks The Celebs Are Utilizing high security Door locks

Five Killer Quora Answers On Couch L Shaped Couch L Shape

Built In Cooker Tools To Make Your Daily Life Built In Cooker Trick That Should Be Used By Everyone Be Able To built in cooker

5 Laws That Anyone Working In Vacum Robot Should Know Robot Vacuum Cleaner Best Buy

A Brief History Of French Door Repair Services In 10 Milestones French Door Repair Services In (sundaynews.Info)

10 Things That Your Family Taught You About Online Sports Calculator Online Sports Calculator, oren-expo.ru,

25 Amazing Facts About Buy A Retro Refrigerator Gefriertruhe Testsieger

How To Create An Awesome Instagram Video About Railroad Settlement railroad settlement interstitial lung Disease

10 Facebook Pages That Are The Best Of All-Time About Sweeper For Sidewalks At A Great Price Akku Hochentaster Kettensäge

5 Killer Quora Answers To SCHD Semi-Annual Dividend Calculator Schd semi-annual dividend calculator

Guide To Robotic Vacuum Cleaner Self Emptying: The Intermediate Guide For Robotic Vacuum Cleaner Self Emptying Robotic Vacuum Cleaner Self Emptying

5 Killer Quora Answers On Conservatory Water Damage conservatory water damage (https://forums.ppsspp.Org/member.php?action=profile&uid=5588415)

What's The Job Market For Fascia And Soffit Maintenance Professionals? Fascia And Soffit Maintenance

The 10 Most Terrifying Things About Window Renovation Window Renovation [md.un-hack-bar.de]

11 "Faux Pas" That Are Actually Acceptable To Use With Your U Shape Sectional Sofa Chaise Sectionals

5 Killer Quora Answers On Professional Door Handle Repair Professional Door Handle Repair

See What Electronic Door Locks Tricks The Celebs Are Using electronic door locks (https://dokuwiki.stream/wiki/A_Rewind_A_Trip_Back_In_Time_What_People_Talked_About_Mortise_Lock_Replacement_20_Years_Ago)

What's The Current Job Market For Double Glazing Leak Repair Professionals Like? Double Glazing Leak Repair

5 Killer Quora Answers On Built In Oven And Hob built in oven And hob

Five Killer Quora Answers On Best Door Handle Repair best Door handle repair

20 Fun Informational Facts About Handmade Sofa Traditional Handmade Sofa

The Top Companies Not To Be Follow In The Window Repair Industry House Window Repair

See What Door Lock Replacement Service Tricks The Celebs Are Utilizing Door Lock Replacement Service

Positive site, where did u come up with the information on this posting?I have read a few of the articles on your website now, and I really like your style. Thanks a million and please keep up the effective work.

9 . What Your Parents Teach You About Tilt And Turn Window Repair Specialist Tilt And Turn Window Repair Specialist (hackmd.okfn.de)

Guide To Espresso Machine With Steam Wand: The Intermediate Guide For Espresso Machine With Steam Wand Espresso Machine With Steam Wand (http://volleypedia-org.50and3.com/index.php?qa=user&qa_1=Pairsugar45)

A Look At The Ugly Real Truth Of Intergrated Electric Oven Integrated Electric Oven

15 Things You Don't Know About Door Hinge Issues Residential Door hinge Specialist

What's The Current Job Market For Asbestos Lung Cancer Louisiana Attorney Professionals Like? Asbestos Lung Cancer Louisiana Attorney

The 10 Most Terrifying Things About Guttering Repairs Guttering repairs

15 Best Guttering Contractors Bloggers You Should Follow Best Guttering

15 Ideas For Gifts For Those Who Are The Best Cat Flap Installer Lover In Your Life cat flap with timer installation

See What Glazing Near Me Tricks The Celebs Are Using glazing near Me

Ovens Integrated 101"The Ultimate Guide For Beginners interior Design

Your Family Will Be Grateful For Getting This Summer Tires 205 55 R16 Sommerreifen Testsieger 2024

5 Things Everyone Gets Wrong On The Subject Of Automatic Vacuum Cleaner And Mop Robot Robotic Vacuum Cleaners

The 10 Most Terrifying Things About Asbestos Lung Cancer Louisiana Symptoms asbestos lung cancer Louisiana symptoms

Why We Our Love For Integrated Electric Ovens (And You Should Also!) Integrated Oven Electric (Https://Nerdgaming.Science/Wiki/20_Top_Tweets_Of_All_Time_Oven_Built_In)

How To Explain Glazier To Your Grandparents emergency Glass repair; trade-britanica.trade,

The Best Glazier Near Me Tricks To Make A Difference In Your Life Best glazier near me

See What Vacuum Robot Self Empty Tricks The Celebs Are Using Vacuum Robot Self Empty

See What Top-Rated Tilt And Turn Window Repair Service Tricks The Celebs Are Utilizing Top-Rated Tilt And Turn Window Repair Service

7 Helpful Tips To Make The Most Of Your Repair Window Hinge Mechanism Window Hinge Repairs

20 Fun Details About Commercial Window Repair emergency glass Repair

Misted Double Glazing Solutions Tools To Streamline Your Daily Lifethe One Misted Double Glazing Solutions Trick Every Person Should Be Able To Misted Double Glazing Solutions

See What Same Day Window Repair Tricks The Celebs Are Making Use Of Same Day Window Repair

Railroad Cancer Settlement Tools To Ease Your Daily Life Railroad Cancer Settlement Trick That Everybody Should Learn Railroad Cancer Settlement

A Delightful Rant About Robot Vacuum Good Robot Vacuum

8 Tips To Enhance Your ADHD Psychiatrist Game Private Pay Psychiatrist Near Me

Why Windows Repairs Is Everywhere This Year window and door renovation

What Is The Secret Life Of Handmade Living Room Furniture Sofas

14 Questions You're Uneasy To Ask Cheap Sofas For Sale cheap l shaped Couch

Watch Out: How Buy Washer Dryers Online Is Taking Over And What Can We Do About It Angebote FüR Waschtrockner-Kombinationen - Pad.Karuka.Tech -

15 Up-And-Coming Cheap Fridge Freezer Sale Bloggers You Need To Be Keeping An Eye On Waschtrockner Erfahrungen (Brewwiki.Win)

15 Up-And-Coming 4-In-1 Combination Welding Machine Offer Bloggers You Need To Check Out Wig SchweißGeräT Mit Pulsfunktion

Five Killer Quora Answers On Sofa U Shape Sectionals With Chaise Lounge

Bunk Beds Children's Tools To Help You Manage Your Daily Life Bunk Beds Children's Trick That Every Person Should Learn bunk beds Children's

Think You're Perfect For Doing U Shaped Sofa? Try This Quiz Couch With Chaise - Https://Promovafacil.Com.Br -

Bespoke Aluminium Door Tools To Improve Your Daily Life Bespoke Aluminium Door Trick That Should Be Used By Everyone Be Able To bespoke aluminium Door

What's The Job Market For Diy Window Hinge Repair Professionals Like? Window Hinge Repairs

14 Creative Ways To Spend Left-Over Wall Mount Fireplace Budget Wall-Mounted Fireplaces [Hedgedoc.Eclair.Ec-Lyon.Fr]

Are You In Search Of Inspiration? Look Up Window Specialists upvc window repair

What NOT To Do In The Purchase Grinding Machines On The Web Industry Gewerbliche Schleifmaschinen Online Kaufen

10 Wrong Answers To Common Asbestos Lung Cancer Louisiana Symptoms Questions: Do You Know The Right Ones? Louisiana Mesothelioma Diagnosis

The 10 Most Scariest Things About Car Crash Attorney car crash attorney (trade-britanica.Trade)

the table beds which we have a year ago had already broken down, it is mostly made up of plastic,.

What Double Glazing Cost Experts Want You To Learn quick double glazing Installation

How To Research Comprehensive Mental Health Assessment Online Comprehensive Mental Health Assessment Online

You'll Never Guess This Pull Out Sleeper Sofa's Tricks pull out sleeper sofa

What Is Door Hinge Replacement And Why Is Everyone Dissing It? composite Door replacement

15 Secretly Funny People Working In Window Replacement Home Window Replacement

3 Reasons Commonly Cited For Why Your Conservatory Repair Cost Isn't Working (And How To Fix It) Conservatory repairs

What's The Job Market For Accident Injury Case Lawyer Professionals? Accident Injury Case Lawyer

Five Killer Quora Answers To Asbestos Lung Cancer Louisiana Risk Asbestos Lung Cancer Louisiana Risk

7 Simple Secrets To Totally Rocking Your Oven And Hobs hobs and ovens

You'll Never Guess This Accident Case Attorney's Tricks Accident Case Attorney

홈타이의 가장 큰 매력은 나만의 편안한 공간에서 주위의 시선을 신경쓰지 않고 프라이빗하게 전문가의 정교하고 전문적인 손길을 누릴 수 있다는 점입니다.

Guide To Accident Injury Settlement Attorney: The Intermediate Guide For Accident Injury Settlement Attorney Accident Injury Settlement Attorney

Mesothelioma Lawsuit Louisiana Tools To Help You Manage Your Everyday Lifethe Only Mesothelioma Lawsuit Louisiana Trick That Should Be Used By Everyone Know Mesothelioma Lawsuit Louisiana (https://Www.haywoodloven.top/)

지식을 공유해 주셔서 정말 감사합니다. 제가 찾은 주제는 정말 훌륭했습니다.

지식을 공유해 주셔서 정말 감사합니다. 제가 찾은 주제는 정말 훌륭했습니다.

The Little-Known Benefits Of Toyota Car Key Lost Toyota Car Key

고객이 머문곳으로 자택, 호텔, 오피스텔 등 대구 출장 마사지는 어디서든 편안한 환경에서 맞춤형 환경 서비스를 제공합니다.

고객이 머문곳으로 자택, 호텔, 오피스텔 등 대구 출장 마사지는 어디서든 편안한 환경에서 맞춤형 환경 서비스를 제공합니다.

Guide To Accident Injury Legal Representation: The Intermediate Guide On Accident Injury Legal Representation Accident Injury Legal Representation; Milsaver.Com,

The 10 Most Scariest Things About Cheap Coffee Maker Online cheap coffee Maker Online

Guide To Sash Window Repair Quotes: The Intermediate Guide To Sash Window Repair Quotes sash window Repair Quotes

14 Companies Doing An Excellent Job At Volvo Car Key Volvo Car Keys Replacement

Why Replacement Key For Toyota Aygo Is So Helpful In COVID-19 Toyota Aygo Key - https://hedgedoc.eclair.ec-lyon.fr/s/irgHCsNhtU,

The 10 Most Scariest Things About Toyota Car Keys Replacement Cost Toyota Car Keys Replacement Cost

What's The Current Job Market For Toyota Spare Key Replacement Professionals Like? Toyota Spare Key Replacement (fakenews.Win)

Five Killer Quora Answers To Conservatory Water Damage conservatory water damage

The 10 Most Terrifying Things About Emergency Vandalism Repair Emergency Vandalism Repair

See What Accident Injury Claim Attorney Tricks The Celebs Are Utilizing Accident Injury Claim Attorney

5 Killer Quora Answers To Personal Injury Attorney Personal Injury Attorney, Milsaver.Com,

Accident Injury Claim Attorney Tips To Relax Your Daily Life Accident Injury Claim Attorney Trick That Everyone Should Be Able To Accident Injury Claim Attorney (https://kanban.xsitepool.tu-freiberg.de/)

Guide To Weight Loss Products Online: The Intermediate Guide Towards Weight Loss Products Online weight loss products online

What You Need To Do On This Diy Window Hinge Repair Fix Loose Window Hinge (https://prosto-robota.com.ua)

As I website possessor I believe the subject material here is rattling fantastic , appreciate it for your efforts.

Think You're Ready To Start Doing Railroad Settlement Pulmonary Fibrosis? Take This Quiz mesothelioma Diagnosis

What's The Current Job Market For Back Door Locks Professionals Like? Back Door Locks

Door Hardware Repair Tools To Ease Your Everyday Lifethe Only Door Hardware Repair Trick That Should Be Used By Everyone Learn Door Hardware repair

9 . What Your Parents Teach You About Accident Insurance Claim Lawyer Accident Insurance Claim Lawyer (rant.li)

See What Upvc Door Panel Specialists Tricks The Celebs Are Using Door Panel Specialists

Accident Injury Attorney Tools To Make Your Daily Life Accident Injury Attorney Trick Every Person Should Learn Accident Injury Attorney

Guide To Accident Lawsuit Representation: The Intermediate Guide For Accident Lawsuit Representation accident Lawsuit Representation

아산출장마사지는 아산 전지역 출장이 가능하고 예약후 원하는 장소에서 바로 관리 받을수 있다는 장점이 있습니다 필요한 대기 없이 깔끔하고 편안한 아산출장마사지 서비스입니다.

Five Killer Quora Answers To Asbestos Lung Cancer Louisiana Risk Asbestos Lung Cancer Louisiana Risk (Www.Altonangelico.Top)